Rain didn’t happen too often when I lived in Southern California, but when it did, I always loved the gleam it brought to the garden.

And literally, too—the wide-spreading patches of volunteer nasturtium vines seemed to sparkle with thousands of Swarovski crystals after a good rainstorm.

It’s a sight to behold if you bend down and really take notice…

Sometimes the raindrops roll off the leaves, or bounce as soon as they land, but many will pool on the lily pad-like surface and stand still until a breeze blows them away. They may even form patterns along the veins, as if Mother Earth just finished bedazzling her blanket of nasturtiums.

No matter how hard or how much it rains, they just don’t seem to get wet. And it left me wondering… are nasturtium leaves waterproof?

Understanding how superhydrophobic plants work (the “lotus effect”)

Unlike most leaves in the botanical world, water doesn’t spread and soak into a nasturtium leaf. When water hits the surface, the droplet bursts into many smaller droplets that bounce along until they finally settle or fall off.

It’s an extraordinary adaptation that only a few plants exhibit, the most well-known being the lotus leaf, along with lady’s mantle, prickly pear, taro, rice, and certain cane species.

The extreme water repellency of these plants (or superhydrophobicity, in scientific lingo) is the result of natural evolution to assure their survival.

In the jungles and other wet environments where these plants thrive, sunlight is very limited. Frequent downpours wash dirt and dust onto the plants, leaving tiny particles that prevent light from penetrating the leaves.

Since these particles can interfere with photosynthesis, nanostructures on the leaves inhibit water from absorbing.

What happens instead is the droplets roll across the surface collecting dirt and other contaminants in their path, in effect cleaning the leaves—a phenomenon known as the “lotus effect.”

The lotus effect also protects plants from pathogens (like fungi or algae) that try to adhere to the leaves. And this ultra water repellency helps cleanse the bodies of insects like butterflies, dragonflies, and cicada. Think of it as a biological housekeeping service!

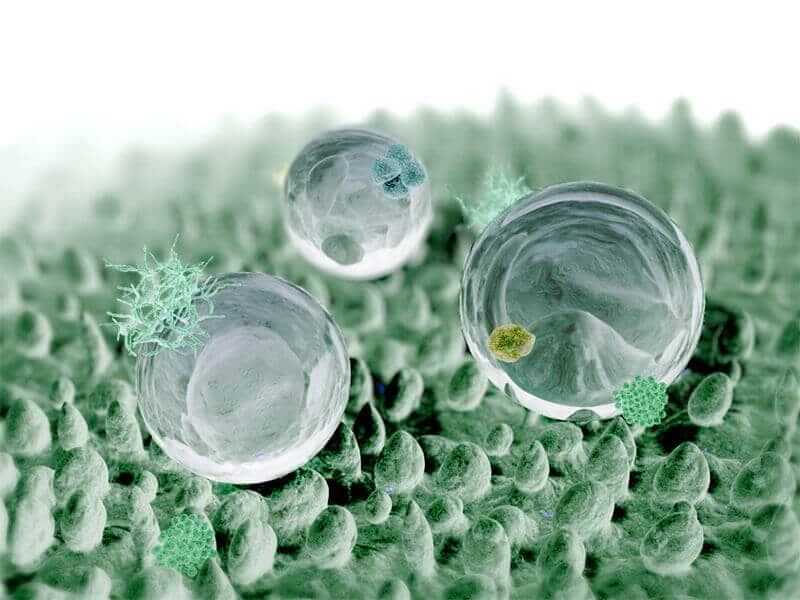

Though nasturtiums look and feel silky smooth, zoom in on a leaf and you’ll find a landscape of microscopic mountain-like structures. Each “mountain” is covered in waxy nanocrystals that are approximate 1 nm (nanometer) in diamater.

The bumpy texture is there for a reason: it’s more water-repellent than a smooth surface would be.

These nanocrystals trap air between the leaf and water droplet, forcing the water to bead and perch on the peaks, rather than sit and spread in the valleys. With nothing to anchor them, the droplets roll around with little contact resistance until they fall off the edge of the leaves.

How is waterproofness measured?

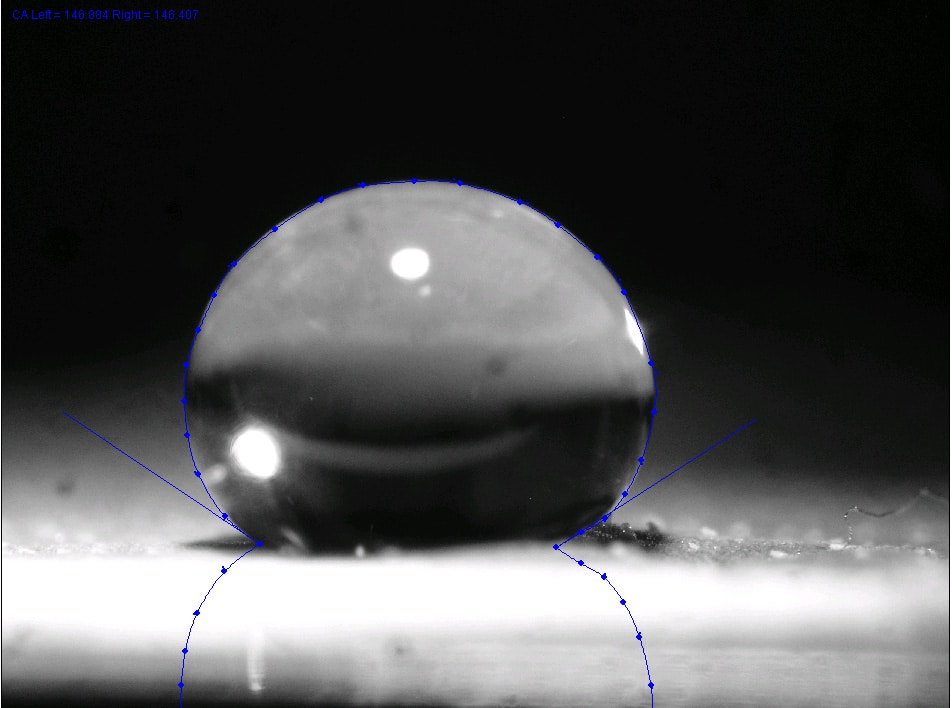

The hydrophobicity of a surface is measured by its contact angle. The higher the contact angle, the higher the water repellency.

Surfaces with a contact angle of less than 90° are referred to as hydrophilic (having a tendency to mix with, dissolve in, or be wetted by water) and those with an angle greater than 90° is referred to as hydrophobic.

Some plants show contact angles up to 160° and are called ultrahydrophobic, meaning only 2 percent to 3 percent of the surface of a droplet is in contact with the surface.

Nasturtium leaves have a contact angle of 145°, putting them in the “superhydrophobic” category (just one step down from ultrahydrophobic).

This means a water droplet creates a perfect “pancake” when it lands on a nasturtium leaf, then quickly springs back up and off the surface.

Can we create a more waterproof surface that replicates nasturtium leaves?

As someone who’s outside a lot, using or wearing a variety of tents, sleeping bags, rain shells, and hiking shoes, water repellency is something I’m always seeking out in gear.

And all of this made me wonder—why aren’t scientists creating the world’s most waterproof fabric from nasturtium leaves? Can they surpass the gold standard of Gore-Tex? (Which is essentially just Teflon-coated fabric.)

Turns out, they’re working on it. An engineering team from MIT has developed the “most waterproof material ever,” inspired by the veins of nasturtium leaves and the wings of the Morpho butterfly.

The new superhydrophobic material (which could eventually be woven into textile fabrics) reportedly repels water 40 percent faster than its predecessors and has a variety of potential applications, including sportswear, lab coats, military clothing, and tents.

Looks like botanically-built adventurewear may be in our future!

This post updated from an article that originally appeared on June 9, 2016.

That was a very interesting article. Very informative and I appreciate the information. Thanks.

Hi Linda,

This is a really wonderful in-depth look into nasturtium leaves!

I coordinate an art studio and garden for very young children, 2-5 years old, in a preschool setting. Nasturtiums are an important part of out garden and nasturtium leaves have a place in the art studio as well- we have made prints, made rubbings, pressed them in a flower press, rubbed their green pigment into paper etc. Observing them after the rain is a favorite of course, and as pipettes are favorite water tools, children can use these to bring drops and squirts of water to the leaves. We are grateful that our nasturtiums have naturalized and come back even after we clear them to plant other things. There are always enough; we can pick them and float them on water, or, a real favorite, a child can to try to balance a drop of water on one and see how far they can walk around the garden. I love how these young people observe, experiment and concentrate! The children have also noticed that the leaves do get “tired” or worn out and loose their water resistance the longer they are played with.

A fun nasturtium factoid, not waterproof related, and brought to my attention by mother, is their name. Nas-turtium literally translates to “nose torture” in Latin. This name is due to their horseradish-like scent. It is a taste too of course, as you know.

I will have a look at other posts of yours and share with my teaching and parenting community as well.

So great!

Hello Betty, I’m so happy to stumbled upon your site! Your writing is so clear and inspiring! Can’t wit to check put your cook book. I’ve been using Nasturtium flowers and leaves for many years and I love to learn more about this humble plant and flower.

Thanks again,

I’ll be featuring my recipe using Nasturtium leaves harvested from my kitchen garden on Monday night at 8 pm on Facebook, Livestream, Mother Zen Chef

This waterproof material would with a 100% probability, lead to a breakthrough that would eventually be followed by a use of it in a way that would lead to an international incident if fallen in the wrong eyes. Of 1 particular person in the world I mean.

This is really cool! I’m growing them for the first time this year (hoping they’ll take over and blanket a problem area on the side of my house) and I’ll be sure to take a peek at them after it rains 🙂