I have beautiful chickens… and I’m not just saying that because they’re my chickens.

It wasn’t too long ago that they were just a flock of raggedy-looking ladies with cowlicks and bald spots, suffering through their seasonal molts (albeit with dignity).

When I look at them now, with their full and fluffy new coats and bright combs again, I’m amazed at what those ladies went through to shed and regrow all their feathers in a relatively short period of time.

Have you ever wondered what actually happens during a molt? How and why they start, and when those pin feathers unfurl into beautiful plumes?

Though we may not always see it clearly, molting is a timed sequence of events that our flocks go through every year. Here’s a look at what exactly happens when a chicken molts.

How a chicken knows when it’s time to molt

All birds are born with a circadian clock—an internal time-keeper, you might call it. This circadian clock tells the bird the right time to lay, the best time to molt, and in some species, the proper time to fly south for the winter.

Throughout a bird’s life, the circadian clock adapts itself to the environment and falls in rhythm with not only the amount of light present in any given season, but also the intensity of that light.

This is why birds living along the equator still molt, despite the days and nights staying consistent year-round. Tropical climates all have wet seasons and dry seasons, with subtle changes in the intensity of sunlight that the birds are sensitive to.

The circadian clock is located in a bird’s pineal gland near the front of the brain. The pineal gland is “wired” to the eyes, which helps the bird perceive light. It’s the same organ responsible for the drop—and renewal—of egg production in fall and spring.

Telltale signs of a chicken molting

In the Northern Hemisphere, we see the circadian clocks at work when the onset of fall in September brings reduced daylight.

Our hens suddenly hunker down, slow or stop their egg laying, and seemingly break out in pillow fights every night.

To prepare for winter, their bodies are telling them to drop all the old feathers and regrow new ones for better insulation and weatherproofing. (And yes, this still applies to chickens in warmer climates with mild to no winters; they still need a new coat for the rainy season.)

Since feathers are primarily composed of protein, egg production is often sacrificed in order to channel their protein reserves to their new feathers.

Read more: 7 Surefire Tips and Tricks for Keeping Your Chickens Healthy Through Winter

The combination of molting in fall, followed by less daylight in winter, is why your chickens may lay fewer (or no) eggs until spring.

Molting takes a lot out of a chicken, and you’ll sometimes find your flock to be less enthusiastic and energetic during this time.

You might think your chickens are sick when in fact, they’re simply in a molt. They might move at a slower pace or retreat from the flock altogether. They might eat a little less and their combs will shrink or pale in color. Your chickens might even poop less, as their metabolism slows down.

They’ll feed very little on crushed oyster shells, if at all, since they don’t need the extra calcium while they’re on egg hiatus.

Despite their lack of appetite, your chickens should still be drinking from their fountains regularly. If they refuse water, it could be a sign of other health issues.

What to do when a chicken molts

It’s important to maintain a routine during your chickens’ molts to help them get through it more comfortably.

Avoid subjecting them to physical, mental, or environmental stress, such as changing their diets, moving them to new quarters, or introducing new flock members.

If you make your own chicken feed, increase the protein content a little bit to help with feather regrowth. Or, offer your chickens high-protein snacks like dried mealworms, dried grubs, sunflower seeds, hemp seeds, or pumpkin seeds.

If you grow squash in your garden, toss them a pumpkin or winter squash (cut in halves or quarters)—chickens go crazy for the high-protein seeds and tender flesh! It’s a good way to use up any bruised or blemished fruit, or a Halloween carving pumpkin that’s no longer needed. (It’s also a great way to get those dark orange yolks from your chickens once they start laying again.)

In short, picture how you feel when you’re down and out… You probably don’t want to do very much aside from resting, sunbathing, and hoping you’ll get over it soon!

The 3 stages of a molt

For an adult hen, an annual seasonal molt can take anywhere from one month up to six months, with two to three months being the norm.

Your latest molters are also your fastest molters, completing their cycles in as little as one month. These hens are typically the most prolific layers as well, and are most desirable in terms of production birds.

Late molters include Barred Rocks, Plymouth Rocks, Rhode Island Reds, Sex Links, and Easter Eggers.

Your earliest molters will take the longest to regrow their feathers, and generally don’t begin laying again until spring. These breeds tend to lay fewer eggs compared to their quick-molting counterparts.

Think: Cochins, Brahmas, Dominiques, and showy breeds like Sultans and Polishes.

Related: The Big Reason Some Chickens Molt Faster Than Others

Chickens generally molt in a predictable pattern from head to tail and from primary to secondary wing feathers (moving from axial feather to wing tip).

If your chickens are going through soft molts, you might not notice this pattern as it often looks like new feathers grow in place of old feathers right away.

About the only time I notice Rosa Pecks, my Pencil Laced Wyandotte, starting to molt is when her bare bottom emerges in late summer! (Which means she’s probably been molting for a few weeks already.)

But if your chickens are going through hard molts—as Kimora, my intrepid Barred Rock, does every year—it’s truly a fascinating study on the different stages of seasonal molting.

Stage 1 of molting

When a chicken starts shedding her feathers, they’re replaced by brand new ones called blood feathers (or pin feathers).

Blood feathers look like little pins or porcupine quills. They’re so called because they have a blood supply flowing through the spikes (stiff hollow tubes known as feather shafts), similar to the way blood flows through veins.

This blood provides the necessary nutrients to a developing feather. Most of the blood is concentrated in the base of the shaft, while the feather itself is encased in a waxy coating in the tip of the shaft.

Sometimes the shaft will crack or break, causing the feather to bleed.

If you have Cochins or Brahmas, with their abundantly feathered feet, this is fairly common as the pin feathers on your chickens’ feet can snap off from normal walking.

The pin feather stage is very painful for a hen, which is why most don’t like to be handled while it’s taking place.

Stage 2 of molting

You might notice in your hens that the shafts start out as tiny nubs as they’re “pushed out” of the follicles, then become very spiky with a tightly rolled appearance.

As the shafts grow longer, the waxy casing loosens and the shafts take on a “furry” look as the feathers start to emerge from the tip. Oftentimes, a chicken will pull the shafts off her new feathers while she’s preening herself.

Stage 3 of molting

Over the course of the molt and through normal preening, the waxy casing falls off to reveal the new feather.

Chickens look pretty scruffy at this stage in their molts, as they have a mix of old and new feathers falling out or growing back in.

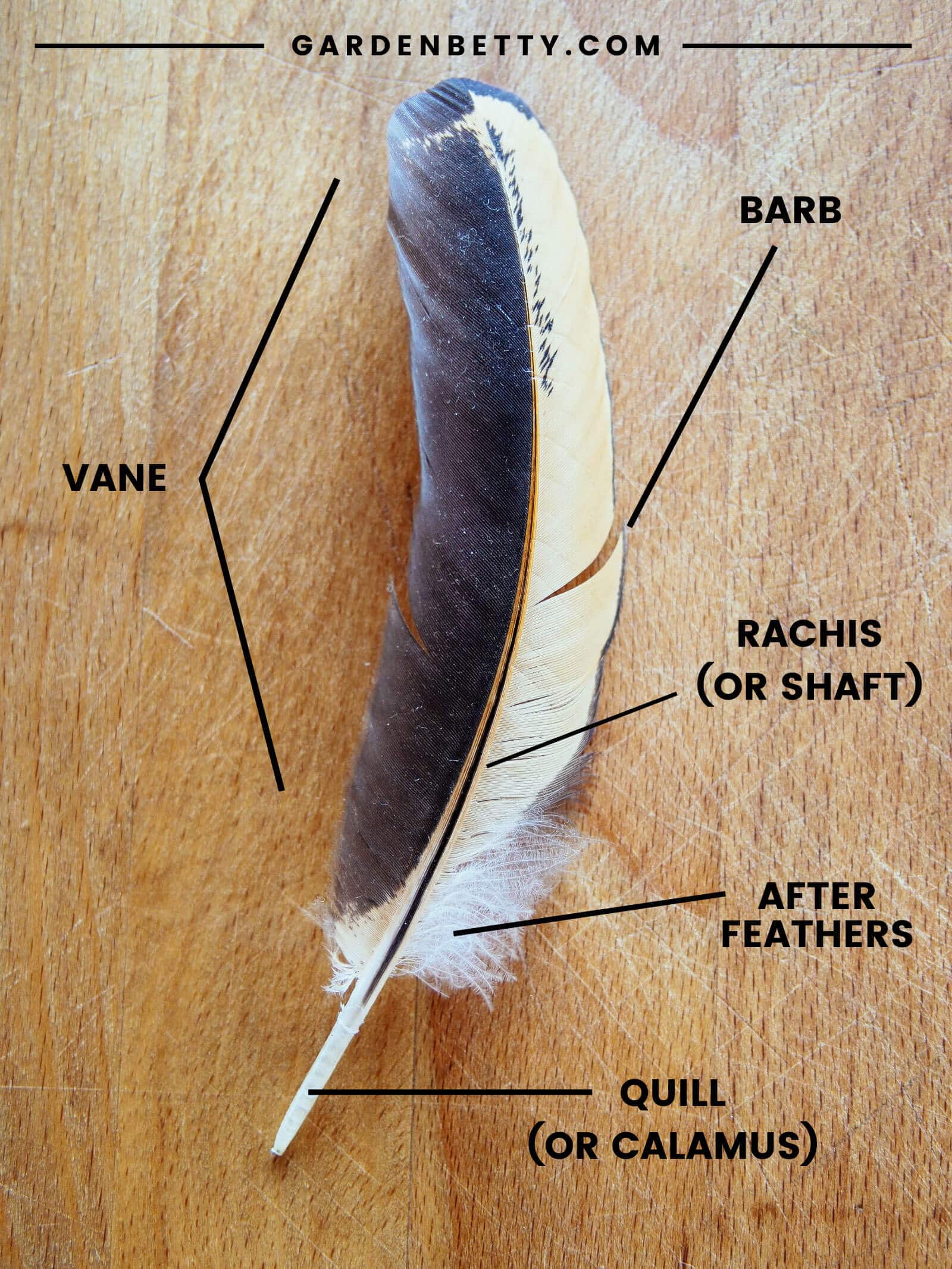

The feather unfurls and the shaft eventually dries up, becoming the quill you’re probably familiar with. (Remember the quill pen from days of yore? It uses the hollow shaft of a bird feather as an ink reservoir.)

Anatomy of a chicken feather

A fully grown feather is a beautiful thing. It’s amazing to think that something so seemingly simple took months to develop!

Newly emerged feathers are vibrant, soft, and glossy, and a hen keeps her coat looking lush with help from her uropygial gland (also known as the preen gland or oil gland).

How chickens keep their feathers soft and glossy

Pull back the tail feathers on your hen and you’ll find a tiny nipple-like nub called a papilla. (I’ll admit that the first time I found this nub, I panicked slightly and thought it was a fatty tumor!)

The papilla secretes a special preen oil—I liken it to a luscious body oil we women might spray on ourselves.

The hen rubs her head and beak against the gland opening, and then spreads the oil all over the feathers on her body and wings and the skin on her legs and feet. Ahhh… instant luxury!

If you’ve ever watched your ladies bury their beaks in their chests, wings, and tails and wondered what they were doing, chances are, they’re preening themselves with preen oil.

At the end of their molts, your hens should be back to their happy selves again, scratching in the dirt and clucking away at the first sign of worms.

More resources to help your chickens get through their molts:

- 7 Surefire Tips and Tricks for Keeping Your Chickens Healthy Through Winter

- Helping Your Chickens Grow Back Beautiful Feathers

This post updated from an article that originally appeared on February 17, 2014.

View the Web Story on chicken molts.

This was such great information! Our flock only has one hen that is over 18 months old and she is dropping feathers like crazy. We thought she’d been getting attacked because our youngest chicken was attacked a few nights ago, but reading this has set my mind at ease. The photos too are really, really helpful! Thank you.

Super informative! Thanks

Wow! This is extremely informative. I ADORE the accompanying photographs; those chickens are gorgeous.

Wonderful pictures and excellent description of this amazing yearly event – thank you!!

I really like your information. do you have literature or reading material that explains this? I used it as valuable information in my scientific writing

I pulled the information from various sources online, including university cooperative extensions and poultry extensions.

Wow, great information Linda. Very interesting. I stumbled on your blog looking for seed starting tips and found other valuable information . I’m considering getting some egg laying hens but I’m unsure about if they would be too noisy for my neighborhood. My city recently passed a law to allow us to keep backyard chickens.. I have raised roosters and hens growing up and I just remember how noisy they can be! Haha

Roosters are definitely noisy, but my hens don’t make any more noise than my neighbor’s dog does (they make much less, actually). If you keep a small flock, noise shouldn’t be a problem. They mostly purr throughout the day and will give a loud BA-BAWK after laying to announce it to the world!

RT @theGardenBetty: How and why a hen goes through an annual molt: Stages of Seasonal Feather Loss and Feather Growth http://t.co/38SBoqASw…

How and why a hen goes through an annual molt: Stages of Seasonal Feather Loss and Feather Growth http://t.co/38SBoqASwD #homesteading

It starts with sunlight (or lack thereof)… Stages of Seasonal Feather Loss and Feather Growth http://t.co/vUNJvMr47C #poultry #molt

Lessons from my backyard chicken coop: Stages of Seasonal Feather Loss and Feather Growth http://t.co/Dv8TSg6A9p #homesteading

Annie Beck liked this on Facebook.

Have you ever wondered why and how a molt happens? Stages of Seasonal Feather Loss and Feather Growth http://t.co/auBHgQrchr #homesteading

I wish we could have chickens! They are so cute…

What happens before, during, and after a chicken molt: Stages of Seasonal Feather Loss and Feather Growth http://t.co/fb5uOtG62v #poultry

I really like the color of your chickens!

Thank you!

Katie Boué liked this on Facebook.

Stages of Seasonal Feather Loss and Feather Growth: I have beautiful chickens… and I’m not just saying that be… http://t.co/hsbFT42wxA

Blogged on Garden Betty: Stages of Seasonal Feather Loss and Feather Growth http://t.co/sqB2UUnn8G